What Makes a Barn Feel Welcoming? And What Quietly Pushes People Out?

On MLK Day, we take a reflective look at how equestrian sport’s narrow traditions and unspoken rules shape who feels they belong.

The horse world likes to think of itself as welcoming. We talk about how horses don’t care what you look like, where you come from, or who you are, only how you show up for them. And while that’s true of horses, it hasn’t always been true of the spaces built around them.

On Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, we’re reminded that progress isn’t just about good intentions. It’s about honestly examining systems, cultures, and traditions—and asking who they serve, and who they quietly exclude.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” In the equestrian world, exclusion rarely looks like someone being turned away at the gate. Instead, it shows up in subtler, more insidious ways — through language, assumptions, traditions, and gatekeeping that collectively create a sport that remains strikingly narrow in who feels they belong.

Canva/CC

The Horse World Has a Diversity Problem, and We Know It

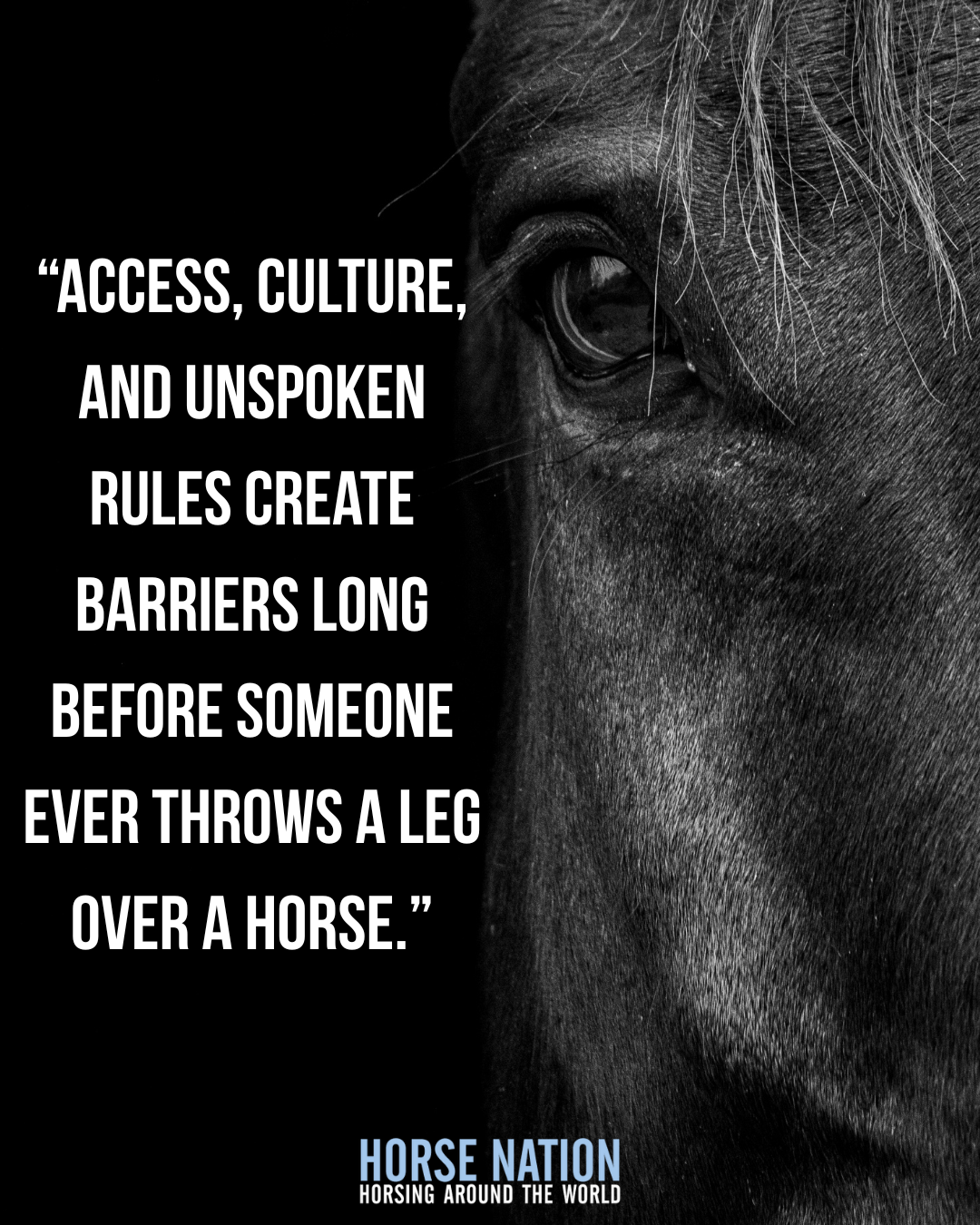

This isn’t a new conversation. Horse Nation has addressed it directly before, acknowledging that equestrian sport (particularly in its competitive forms) remains overwhelmingly white, affluent, and insular. Eventing, dressage, hunter/jumper, barrel racing, mounted shooting, any discipline you can think of all reflect this reality to varying degrees. It’s not because people of different backgrounds don’t love horses. It’s because access, culture, and unspoken rules create barriers long before someone ever throws a leg over a horse.

As Eventing Nation has pointed out, when you look around a start box or a schooling ring and ask, “Where is the diversity?” the uncomfortable answer is often: it’s largely absent. And absence isn’t accidental — it’s the result of systems that replicate themselves over time.

Barns are where those systems live and breathe.

Language: Who We Assume Is “One of Us”

Language is one of the earliest signals of belonging — and exclusion. In many barns, conversation assumes a shared background:

- That everyone grew up around horses

- That everyone knows the lingo

- That everyone understands the unspoken rules

When riders casually reference expensive equipment, elite shows, or childhood access as if those things are universal, it sends a quiet message about who the sport is for (and who it’s not for). Newcomers who don’t share that background may not hear hostility, but they hear distance.

King reminded us that dignity begins with recognition. “All labor that uplifts humanity has dignity and importance.” Yet too often, the horse world assigns value based on polish, pedigree, or perceived legitimacy rather than curiosity, commitment, or care.

Assumptions: The Invisible Barriers

Many equestrian spaces operate on assumptions so deeply ingrained they’re nearly invisible:

- That newcomers can afford lessons, shows, and gear

- That everyone has transportation, time, and financial flexibility

- That everyone comes from a family or culture where horses were accessible

When barns assume everyone arrives with the same resources, they unintentionally reinforce a culture that favors those who already fit the mold. Others may be present, but they don’t feel seen.

This is how exclusion persists without anyone ever saying, “You don’t belong here.”

Africa Images. Canva/CC

Traditions: Comfort for Some, Walls for Others

Tradition often is treated as sacred in the horse world. And many traditions are worth preserving — horsemanship, mentorship, respect for the animal. But when tradition becomes synonymous with resistance to change, it also can become a gate.

Phrases like “That’s just how it’s done” or “This is how it’s always been” are often used to shut down questions rather than invite conversation. For those who don’t already feel at home, tradition can feel less like heritage and more like a locked door.

Dr. King warned against this kind of stagnation: “Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable.” Inclusion requires intentional effort, not nostalgia.

Gatekeeping: Quiet, Constant, and Effective

Gatekeeping in equestrian sport is rarely explicit. It doesn’t need to be.

It lives in:

- Dismissive responses to beginner questions

- Judgments about equipment choices or riding style

- The idea that legitimacy must be earned before belonging

These moments accumulate. Over time, they tell people — especially those who already feel like outsiders — that this space wasn’t built with them in mind.

And when people leave, we often shrug and say, “It’s not for everyone.” But the better question is whether we made it that way.

Canva/Somogyvari/CC

What MLK Day Asks of the Horse World

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. didn’t ask people to be comfortable. He asked them to be honest. To examine systems, not just intentions. To recognize that exclusion can exist even in places that see themselves as good and well-meaning.

If the equestrian world truly believes horses are for everyone, then barns must become places where people are welcome first — before credentials, before polish, before proving themselves.

That doesn’t require grand gestures. It requires attention. Listening. Curiosity. A willingness to question who our spaces serve and who they don’t.

On MLK Day, that reflection matters, because dreams of inclusion don’t survive without action, and progress doesn’t happen unless someone is willing to notice what’s missing.

And in too many barns, what’s missing is still painfully clear.