Horses in the Circus: Equestrian Girl Bosses

Journey back with us as we take a peek behind the curtain of the greatest shows on earth. This week, we check out a few equestrian girl bosses of the center ring.

From Hilda Nelson’s Great Horsewomen of the 19th Century in the Circus:

“…generally speaking, a woman, when she acquires the taste and the passion [for equitation], ordinarily shows herself superior to a man; I say this at the risk of wounding the self-esteem of men.

One of nine children born in Ireland to a horse breeder and trainer, Louisa Woolford began performing at Astley’s Amphitheatre when she was very young and continued to perform until after the birth of her third child with husband and performance partner, Andrew Ducrow.

According to a quote from an Andrew Ducrow obituary in a London Dead Blog post: “ … Miss Woolford … before she became Mrs Ducrow was for a long time the chief attraction of his theatre, and drew crowds by the accustomed gracefulness of her action, and the skilful management of her steed. [She] was very early a debutante at Astley’s, and many theatrical people of about thirty years standing will remember her at the Amphitheatre under Astley’s management as a little girl with a long crop, and of intelligent and pretty manners.”

Though little of her life is known, Louisa undoubtedly left an impression on everyone who watched her perform, including Charles Dickens.

From Sketches by Boz: Illustrative of Everyday Life and Everyday People:

“Another cut from the whip, a burst from the orchestra, a start from the horse, and round goes Miss Woolford again on her graceful performance, to the delight of every member of the audience, young or old.”

One of her acts, “The Tyrolean Shepherd and Swiss Milkmaid,” was a pas de deux performed with her husband. While standing on the backs of circling horses, the two acted out the pursuit and wooing of a ‘fair peasant,’ complete with a lovers’ quarrel and reconciliation scene. —Britannica

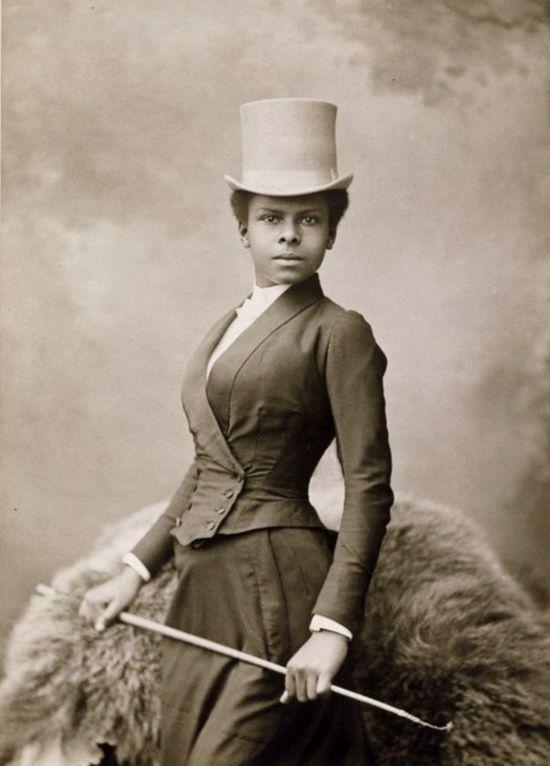

Almost fifty years later, a new breed of horsewomen emerged on the scene. Highly trained in dressage, the haute école écuyère were a mysterious bunch. Many performed under stage names, and little is known of their lives outside the circus aside from the fact that they came from all walks of life and socioeconomic strata.

Among them was Selika Laszevksi. Only six photographs of her exist, now housed in the collection of the French Ministry of Culture. The notes that accompany the original negatives state Selika was a horsewoman who rode haute école at the Nouveau Cirque on the rue Saint-Honoré.

There was also Elvira Guerra. Born in 1855 to circus performer Rodolfo Guerra, Elvira most likely began performing at a very young age. In 1882, The Times reported on Hengler’s Grand Circus, ‘..the terpsichorean powers of the pretty horse “Sylvan”, admirably controlled by Mlle Elvira Guerra.’

Elvira also became the first woman to represent Italy in the Olympic Games, competing in the “hacks and hunter combined” at the 1900 Summer Olympics atop her horse Libertin.

Photo courtesy of The Schoolmistress.

Anecdotal sources state Caroline Loyo arrived in Paris with a single horse where she garnered a reputation for taming unruly animals and taking part in improvised horse races.

After training with François Baucher, she made her debut in Cirque Olympique, run by a Venetian family of equestrians called the Franconi. She would eventually perform in France, Germany and England and capture the attention of one of the most successful painters of the 19th century, Alfred Dedreux.

Holzschnitt “Madam Loyo at Niblo’s Theatre.” published in Gleason’s Pictorial, an illustrated Boston newspaper, in May of 1851.

In fact, the haute école écuyère would become muses for many famous artists.

The Biodiversity Heritage Lab states, “People especially loved women who performed feats on horseback, viewing these women as dominant and yet feminine at the same time, able to control the mighty beast and look dainty while doing so.”

Born into poverty as Marie-Clémentine, French artist Suzanne Valadon was also a talented acrobat and accomplished equestrian. At the age of fourteen, she began working at the Cirque Molier, where she caught the eye of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, modeling for him many times. She would later go on to pose for both Degas and Renoir, despite her circus career ending prematurely after a fall from the trapeze.

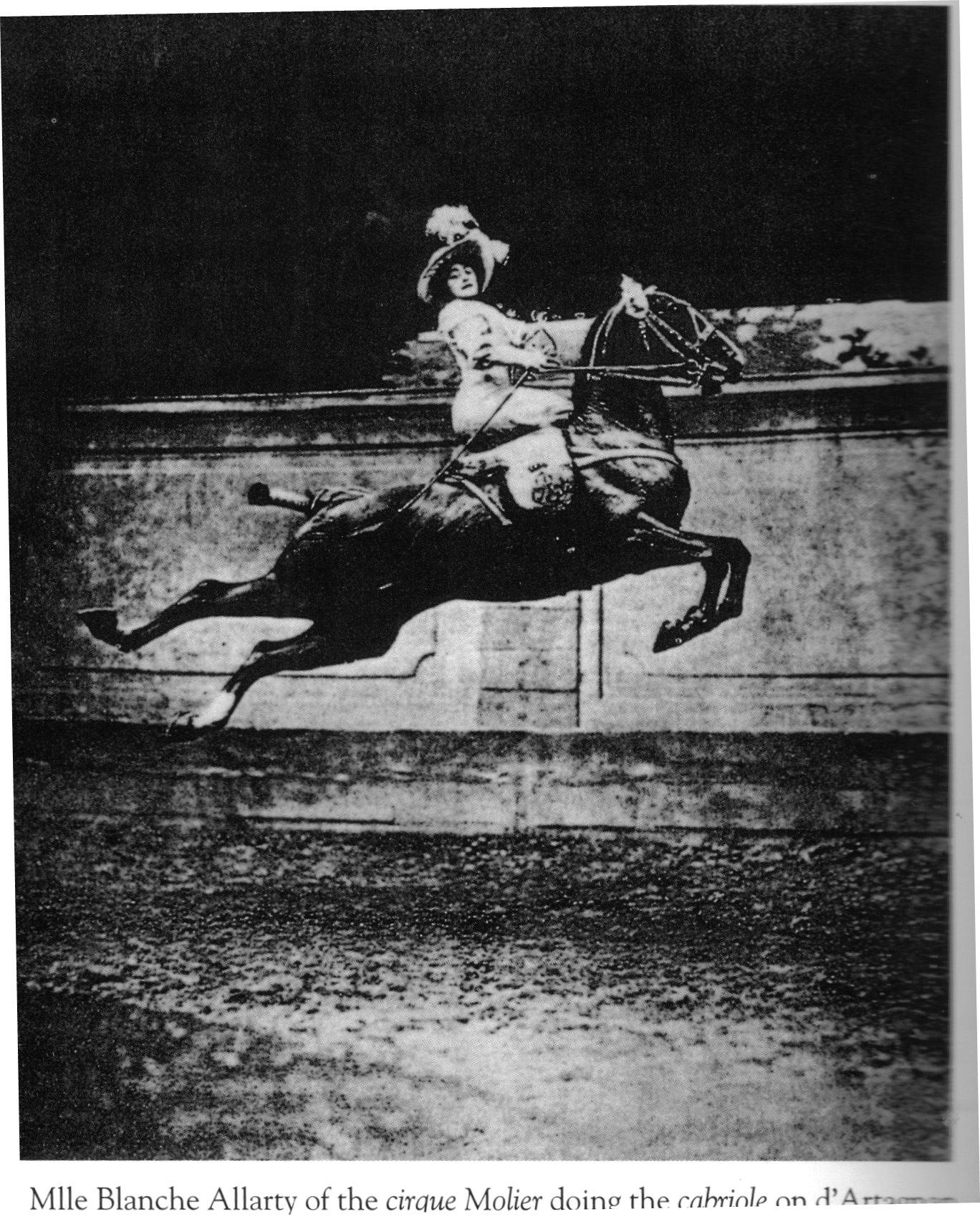

Last but not least, Blanche Allarty, the daughter of an amateur horseman, joined the circus when she was only thirteen years old under the tutelage of Ernest Molier — the man that would very shortly become her husband.

She specialized in vaulting and was known for “voltige à la Richard.” Unsaddled and unbridled, the act began with the rider running alongside the horse while simultaneously jumping cavaletti. After vaulting onto the horse’s back, the rider then stood upright as the horse continued to jump. Blanche was the first person to complete the trick, after it’s creator, Davis Richard, died during his attempt.

Sources say Blanche trained her own horses, including her most famous, D’Artagnan, that could reportedly complete a lançade and a cabriole simultaneously. Blanche became one of the most infamous French ecuyère of haute école and toured worldwide, including New York where she was given the nickname, “The Centauress.”

Photo courtesy Great Horsewomen.

Go Riding.

Amanda Uechi Ronan is an author, equestrian and wannabe race car driver. Follow her on Instagram @uechironan.