Thoroughbred Logic, Presented by Kentucky Performance Products: Improving the Off Track Canter

“The turns are what make it harder, so aim for straight line canters and efficient down transitions — even if that means you only have a few strides of canter.”

Welcome to the next installment of Thoroughbred Logic. In this weekly series, Anthropologist and trainer Aubrey Graham, of Kivu Sport Horses, offers insight and training experience when it comes to working with Thoroughbreds (although much will apply to all breeds). This week ride along as Aubrey shares her logic on how to improve the canter.

This past weekend, I hosted the first of hopefully many Thoroughbred School Clinics at my now home farm in Lansing, NY. The concept for Thoroughbred School is pretty simple — build a curriculum of activities and clinics to help teach the nuances that enable capable riders to better pilot Thoroughbreds. At this first outing, the clinic classes were fun, the riders came in open minded and ready to learn, and the horses traveled better, jumped better and were game and happy for the whole set of experiences. Fantastic. Now to set up a way to make this work in semesters both virtually and in person. Stay tuned.

Discussing how cantering on gallop lanes helps build the ability to sit and turn in the arena. Photo from the recent Thoroughbred School Open House by Lily Drew.

These clinics often are super helpful for pointing out the patterns that I need to address in both my teaching and these articles. Great. They also give me space to demonstrate the concepts that I think are relevant to most of the participants. So, we kicked off the day with a discussion and a set of demos about how to improve the “off track” canter.

On the track, most Thoroughbreds pull through their forelimbs and shoulders. Their gallop is long, often-low, and hopefully fast. In addition to racing and breezing, they do work out through slower gallop sets, canters, and trots where they are more held together by exercise riders. Some even cross train over uneven terrain. Yet, when put through their paces, the work rarely if ever, involves turning relatively tightly and then turning again after five to 10 strides (in the way our arenas ask us to ride). Instead, they school on the track, both leads, both directions but with long lines and sloping turns. Thus, Thoroughbreds often come off the track unaccustomed to tight turns and with a forehand that is stunning and muscled, but a hind end that often could use some bulking up and general strengthening.

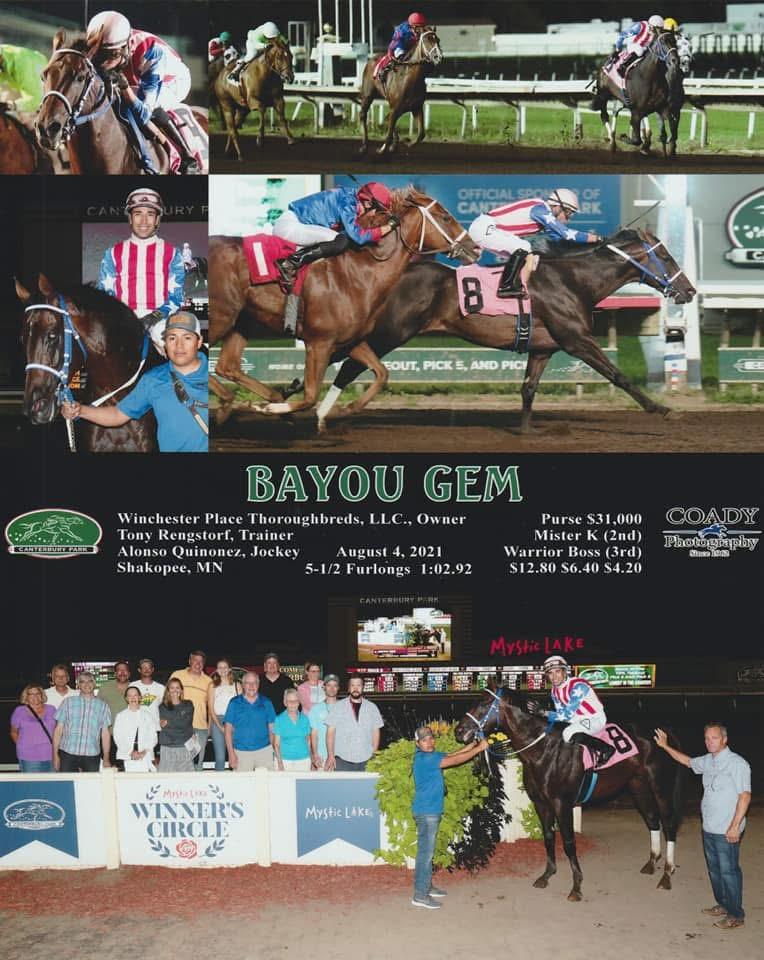

Win photo of Bayou Gem, a horse I rehired a few years back — now a lovely eventer. Photo from Winchester Place Thoroughbreds.

In short, much of the early days of their retraining focuses on shifting the muscle priority from the forehand to the hind end. And as such, that strengthening builds balance and the ability to hold their gait, cadence and uprightness through the types of turns that we sport horse folks ride daily.

Back to the clinic: I knew that some participants had been struggling to get or to balance the canter on their somewhat recently retired racehorses. In order to address it, I brought out my horse with similar issues. North (Star Redemption) is a handsome, rangey five-year old who arrived about a month ago. He had some restarting off the track and came here to find his new home. The work that he received before set him up for a nice balanced trot and the understanding of moving off pressure — all good. But my small arena (the indoor is effectively a 20×40 dressage arena) made it tough for him to hold a balanced and steady canter.

North has always had pretty OK canter transitions — that’s not the challenge. Rather, once in the gait and in a smaller arena, he has struggled to sit through his hind end and balance through the turns. Riding in my arena is effectively like this: get canter, turn, straight for like five strides, turn, turn, straight for like five strides, turn, turn… you get the gist. For horses without perfect canter rhythm and balance, this is not only tough, but also quite frustrating/nerve-wracking. They are unsure of their balance and also are trying really hard not to compensate and hold themselves up with speed.

Add to that that for a rider trying to make those turns in the small arena, it is very difficult not to give into the seduction of the inside rein. And it is really hard as a trainer to convince someone that, even at speed, the horses will turn best and most balanced when you soften and lift the inside rein and use outside aids and turn your hips instead. But that’s tough. The green horses already are leaning, they’re already wanting to spin into a higher gear to hold their balance and stay upright. And it sure doesn’t seem like they’re going to turn unless you tell them to clearly — with that dreaded inside rein.

But they will turn — and they’ll do so even better with increasing balance from the outside aids. OK, that’s one thing. But even getting on your outside aids might not quite develop a perfectly clear three-beat canter. So what to do then?

North has been increasingly building up his hind end at the trot and that has undoubtedly helped his canter. Photo by Lily Drew.

1. Build strength in the trot

To improve the canter, work on improving the trot. The more the horse can put their hind end comfortably under them and learn to sit and balance in their two-beat gait, the more this will translate to their canter work. For some green Thoroughbreds, this means that I will test their canter for the first ride or two and then spend a few weeks not asking for it at all. Instead, I’ll work a couple days a week at the walk and trot, teaching them to push from behind and use their hind limbs to balance and to hold the pace. By the time I ask for the canter again, it often is improved vastly.

*Walking and trotting hills will also help here too.

2. Trot to canter transitions

While we’re aiming for better balance and rhythm in the canter, the strength and confidence that is needed for that is also built in the up transition. Even in small spaces you can ask for the canter and, once it’s confirmed, keep cantering down a long side. Importantly though, without pulling (sit up, half halt with your leg and core), and toss in a down transition before asking them to turn. Trot a lap, regain good balance and cadence, and then up transition and canter a longside again. The turns are what make it harder, so aim for straight line canters and efficient down transitions — even if that means you only have a few strides of canter.

Limelight (No Lime, owned by Norm Johnson) is an absolutely lovely dude who is working on using his transitions to build his strength and balance. Photo by Lily Drew.

3. Canter in long straight lines (preferably outdoors).

I am lucky in that this property is on a slight grade and has long, straight paths along its edges. We added to those by mowing straight trails through the hayfield for exactly this purpose. To build strength and balance in horses who struggle inside at the canter, I take them out to the gallop lanes, walk or trot to the bottom of the property and canter them north. I’ll hop in my half seat, bridge my reins and let them find their balance and speed (without hitting mach-5). The important thing in this exercise is that I try to just let them canter at a medium pace for as long as possible — here that means about a 1/4-1/3 a mile depending on if I’m on the lane or the easement. This allows them to find their balance with a regular sized rider over regular terrain (aka not a jockey and not on a groomed track). But it also takes the turns out of the situation entirely and thereby vastly reduces stress on everyone.

North showing off his straight line canter sets while I bridge the reins and stay with him. Photo by Lily Drew.

4. Practice in-gait transitions

In the long lines discussed above there’s another exercise that’s helpful: With an ample path ahead of you, attain a pleasant speed of canter and stabilize it there. I’d hold that for around 10 strides or so if not a bit longer. Then push the gait a few miles an hour faster. Try to not let them get low, fast and long — but rather, aim for an uphill canter that is bouncier and bigger, covering more ground without becoming a flat-out gallop. To do so, you need to keep leg on, control the canter with your core, and keep a soft, but steady hand (I like to bridge my reins and lay them on the neck). Once you have the bigger pace and step, stabilize that cadence and hold it for 10-plus strides. Then open up at the hips, sit up and widen your chest and engage your lower core with leg on to bring them back to the original pace. Hold there for 10 stable strides and then increase the pace and stride length again. Back to the original pace. Rinse. Repeat. Then give them a good pat an equally good walk break.

Uphill much? North increases his pace correctly as I close my hip angle in a demonstration about in-gait canter transitions. Photo by Lily Drew.

The combination of these exercises has a fantastic knock-on effect. They build the horse’s strength sure, but they also build the pairs’ confidence in the ask and in each other (specifically making a rider more comfortable with speed and how to slow it down without pulling). Then add to that positive cycle that the new strength promotes better balance. That better balance built in straight lines ironically then enables said ex-racehorse to take their turns slower and more upright. So when in a couple weeks you want to test the canter in the small arena again, you’ll find that you have better, clearer three-beat cadence and a horse that is markedly improved in sitting and balancing through the corners.

(North is pretty much the perfect student here and I’m thrilled with how far he has come in such a short time. Now to get this kid out eventing.)

So go ride folks, and enjoy the long canters that will help you build up for a winter that is perhaps spent doing more turning inside than galloping in the fields.

Elevate® Maintenance Powder

Fight back against seasonal vitamin E deficiencies.

Elevate® Maintenance Powder was developed to provide a highly bioavailable source of natural vitamin E to horses. Multiple research studies have shown that vitamin E is often deficient in the diets of horses that do not have access to continual grazing on fresh green grass, or those grazing on dormant winter pastures. Performance horses with demanding workloads, growing horses, and seniors have higher requirements for vitamin E, making deficiencies a more common occurrence. Studies reveal that horses who are deficient in vitamin E are at a higher risk for developing neurological and muscle diseases. Don’t let a lack of natural vitamin E put your horse at risk; supplement with Elevate this winter to ensure your horse gets the vitamin E needed to thrive.

The horse that matters to you matters to us. Not sure which horse supplement best meets your horse’s needs? Kentucky Performance Products, LLC is here to help. Contact us at 859-873-2974 or visit our website at KPPusa.com.