Thoroughbred Logic, Presented by Kentucky Performance Products: Over at the Knee

“Over at the knee” — conformation flaw or functional detail? 🤔 Read on for what it really means for soundness and performance.

Welcome to the next installment of Thoroughbred Logic. In this weekly series, Anthropologist and trainer Aubrey Graham, of Kivu Sport Horses, offers insight and training experience when it comes to working with Thoroughbreds (although much will apply to all breeds). This week ride along as Aubrey shares her logic on what it means if a horse is over at the knee.

In this fun day and age, the fates and careers of off-track Thoroughbreds often are determined by two things: how they jog in a straight line and how the look from the side. Jog video gives us soundness (hopefully) and movement, and the conformation shots provide well… conformation.

A lot of folks look at those images and see “is it pretty?” or does it “look like a_(insert discipline)_ horse?” And then they’ll send it to their trainers. That’s good. Do that.

Tobi (JC Fernando) has pretty textbook legs and makes taking conformation photos easy. Photo by Lily Drew.

Trainers with a good eye will take in the whole horse and its body’s angles and alignment, its eye, and then they’ll begin looking from the bottom up. Who cares if it’s the most stunning thing you have ever seen if it might have issues in the feet or legs? So they start there. They’ll look at hoof angles. Yes, you can fix those, but good feet never hurt. They’ll look at the ankles and see if they can see edema or rounding, look up the tendons for bows, and then look at all visible joints for any swelling or abnormalities. That’s all a totally fair exercise.

Horses straight from the track are often “track fit” and slicked out like a greyhound, so it’s easy to see the literal bones and muscles on which you will build their second career.*

*I’m not saying track horses are skinny. Some are, but most are in proper, athletic running condition. There’s a difference.

But the point here is that when they’re race fit, you can really see the foundation you’re getting, and if you squint, you can imagine it let down, with a softer more full topline, and a bit more of a dad bod, ready to head out and gallop around a cross country run (or barrel pattern, or canter down the hunter lines… you get my point).

Indy (Star Player) doesn’t have absolutely perfect conformation (he’s slightly over at the knee), but he always has been easy to imagine into the role he now successfully plays as an eventer. Photo by Lily Drew.

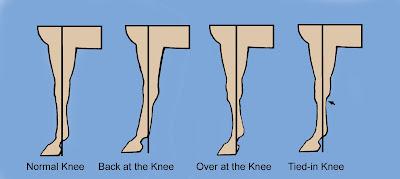

One of the things that arises while looking these horses up and down and assessing how their various bones and muscles and tendons are put together is the way in which their front legs appear from the side. When taking a look at the knee, there are a few options:

- Normal (forearm lines up nicely to the cannon bone)

- Behind -or back- at the knee (rare in racehorses but where their knee buckles backwards a bit)

- Tied in at the knee (where the cannon bone is narrower towards the knee than it is at the ankle),

- Over at the knee (where the leg does not fully straighten).

Knee alignment from the side. Visual from The Equinist.

Back at the knee horses contain risks for high impact careers, so they’re relatively rare in racehorses. Under severe physical stress and exercise (running and jumping), the condition can cause issues for the tendons and ligaments attaching at the knee, thereby creating knee chips, ligament strain and other issues in the forelegs. I’m certain there are horses who are mildly ‘back at the knee’ with a totally fair prognosis, but that depends both on the severity of the angle behind vertical and on the level of physical stress in the second careers they happen into.

On the flip side, over at the knee (or buck kneed) horses might look a little odd, but most of the time, they’re totally fine and can carry on through long, healthy careers. Currently in the barn right now, I have three who are over at the knee — two only slightly and one with a clear “yep, that’s unavoidably there.” The great thing is that largely it usually doesn’t really matter other than impacting the type of movement and length of stride.

Platypus (Ripe for Mischief) is congenitally over at the knee but raced very well (25 times, $68,937 in earnings) and is expected to have a successful second career. Photo by Lily Drew.

Toss the over at the knee thing out to the internet and you’re going to get a lot of “the best jumper I had was over at the knee” and such things. They are unlikely to move like daisy-cutting show hunters due to the lack of full extension of the limb, but they usually can run and jump without any issues. And the legs might not look textbook pretty, but sometimes pretty and functional aren’t always found in the same box.

When Q (Quality Step) came off the track, he was reasonably over at the knee — though hard to see it under the bandages. Photo courtesy of Nations Racing Stable, Q’s former track connections.

Technically speaking, over at the knee horses are either a) born that way (most of the cases) or b) develop this condition from an injury to the ligaments at the backside the knee, where healing has restricted their movement (far less common). For most, the congenital condition is caused by slightly tighter tendons/ligaments on the caudal (back side) of the joint or a tighter joint capsule. Sometimes it is the check ligament that is a bit tighter relative to their bones than average, or sometimes their superficial digital flexor tendon. These foreshortened ligaments/tendons keep the leg from being able to fully straighten and lock straight.

At times, Q’s legs would tremble, but he was sound and quite capable. Photo in the fall of 2022 by Alanah Giltmier.

In moderate cases, this isn’t really an issue. Sometimes, it is barely noticeable in how a horse travels. Even in more serious cases, the prognosis is usually quite good and can be improved with proper shoeing (consult a knowledgable farrier here — it is about bringing the toe back and heel down, yes, but also about controlling where break-over occurs so that they don’t simply knuckle over the shorter toe). In certain cases, horses who are over at the knee will have front legs that tremble. The inability to lock the leg straight means standing for long periods requires constant use of the muscles around the knee to control the position. While not necessarily normal, there’s not a lot of literature out there that finds this symptom to be indicative of a career-ending or limiting condition.

With some muscling, time, and shoeing built around his second career as a general riding horse, Q’s ‘over at the knee’ improved significantly. Photo in the fall of 2023 by Alanah Giltmier.

Sure, there’s info out there that over a the knee horses might stumble more or toe into the dirt when traveling. In severe cases, it could place more strain on the suspensories, sesmoid bones, and DDFT (deep digital flexor tendon). And while none that have come through my barn have been noticeably challenging to keep sound (owing to this conformation), sure — like all things, I bet it is possible.

Importantly, it is worth remembering that when they have raced successfully, they have already been tested. The track has assessed their ability to function on those knees more than any second career will. And if they ran well, flexed fine, and have no visible soundness blips in that jog video, they have already proven that there is speed, stability, and soundness, despite the less-than-beautiful alignment at the knee.

Like any horse, they might need a little more attention to their feet to keep them going at their best. But, the good thing is that while over at the knee conformation can be glaring in a side-focused photo where decisions get made, it does not necessarily impact the quality or athletic ability of the horse you’ll get.

So go ride folks. Here’s hoping the horses are sound and bring joy, despite the alignment of their limbs.

About Kentucky Performance Products, LLC:

Omega-3 fatty acids have been proven to reduce skin inflammation and mitigate allergic response. Contribute delivers both plant and marine sources of beneficial omega-3 fatty acids. Feed one to two ounces per day, depending on severity of the allergy.

Need tips on how to manage allergies? Check out this KPP infographic: Got Allergies?

The horse that matters to you matters to us®. KPPusa.com