George Washington: America’s First Horse Breeder

Long before the White House, there was a stud barn at Mount Vernon.

By the time George Washington became the first President of the United States, he was already well known throughout Virginia, not just as a soldier and statesman, but as one of the most skilled horsemen of his era. His horsemanship was part of the fabric of his life from boyhood through military command and into retirement, and it extended beyond riding: Washington was deeply involved in animal husbandry, including an early and intentional breeding program that helped shape American equine history.

Washington’s relationship with horses began early. As a teenager working as a surveyor in colonial Virginia, he relied on his mounts to travel rugged terrain, pushing both his skill and horses’ endurance. Riding was not just practical, it was a sign of status and capability. In the 18th century, male members of the Virginia gentry learned equitation as part of their social education, and Washington took that seriously.

During the American Revolutionary War, Washington’s horsemanship became part of his legend. He rode at the head of his troops during engagements and endured the hardships of military travel astride famous mounts like Blueskin, a half-Arabian gifted to him by Colonel Benjamin Dulany, and Nelson, a calm chestnut gelding who stayed with him through much of the conflict.

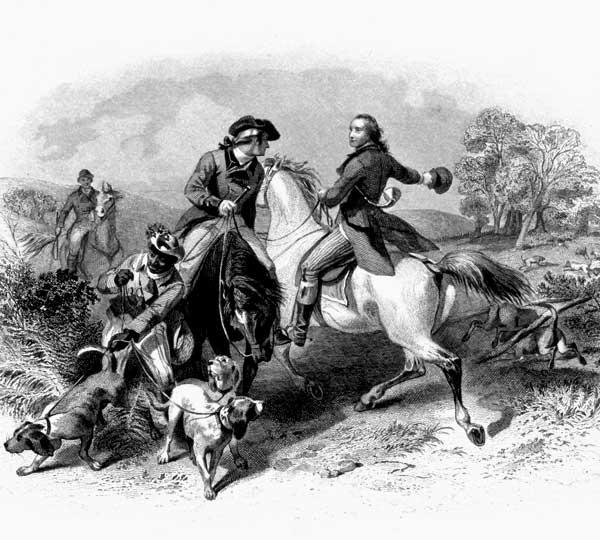

During the American Revolution, Washington was gifted two horses, Nelson and Blueskin (sometimes written as Blewskin), who returned with Washington to Mount Vernon after the war. Photo courtesy of George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

These horses were more than transportation; they carried Washington’s leadership, visibility, and confidence across battlefields where maintaining calm under fire was strategic as well as symbolic.

After the Revolution and during Washington’s tenure at Mount Vernon, his focus on horses evolved from riding prowess to purposeful breeding. He maintained a stud stable at his estate and purchased numerous mares and stallions, investment decisions that were both economic and thoughtful. Washington’s goals weren’t whimsical; he was cultivating stock that could reliably serve farms, transportation, and the growing nation’s labor needs.

Washington once bought 27 army-used mares that had been “worn down,” recognizing that they still had productive lives ahead as broodmares if placed in better care. His agricultural instincts drove him to improve not just the animals on his own land, but to promote better breeding practices for broader American use.

While today Washington isn’t credited with creating a formal “American horse breed” like the later Morgan horse, born around the same time Washington was navigating the early republic, his involvement in breeding contributed to the era’s equine developments.

Interestingly, Washington’s animal program went beyond horses. After receiving a Spanish jack from the King of Spain in 1785 and additional jacks and jennies from the Marquis de Lafayette, Washington began producing mules, the hybrid offspring of donkeys and mares, on a relatively large scale. By 1786, he advertised his “compound” stud services in a Philadelphia journal, promoting crossing donkeys with horses to produce larger, stronger working animals.

Washington preferred mules for heavy labor. He observed they were more durable, less costly to feed, and suited to farm work where horses sometimes struggled. By the end of his life, the number of mules at Mount Vernon had grown significantly. Although Washington didn’t create mule breeding per se, his efforts helped popularize the animal’s role in early American agricultural life.

Washington’s approach to animal breeding reveals a thoughtful mindset that resonates with today’s equine ethics. Washington had respect for temperament & soundness. His records show careful attention to horses with good minds and utility. He did purpose-driven breeding. Washington did not breed for show or vanity; every mating had a practical goal: work, endurance, or improving stock. Washington cared about animal welfare. While 18th-century standards differ from today’s, Washington ensured his horses and mules were cared for in retirement, not simply discarded after service. These principles closely align with modern breeding ethics: prioritizing health, soundness, and suitability for intended work or performance.

Washington’s breeding and husbandry work laid a quiet but meaningful foundation in the early United States. He was part of a generation where horses were essential to communication, industry, and defense and improving them was an investment in the country’s future.

Though the formal American breeds we know, like the Morgan, would be established after his most active years, Washington’s stewardship of horses and mules was part of the broader agricultural evolution that made equine innovation possible.

Today, horse lovers and breeders can still visit Mount Vernon to see draft work demonstrations, wagons pulled by horses similar to those Washington kept, and programs that highlight the estate’s historic livestock heritage. As we remember Presidents’ Day, Washington stands not just as a leader of men, but as a steward of animals whose strength and loyalty helped shape a nation.