Black Cowboys of the American West: The History Hollywood Erased

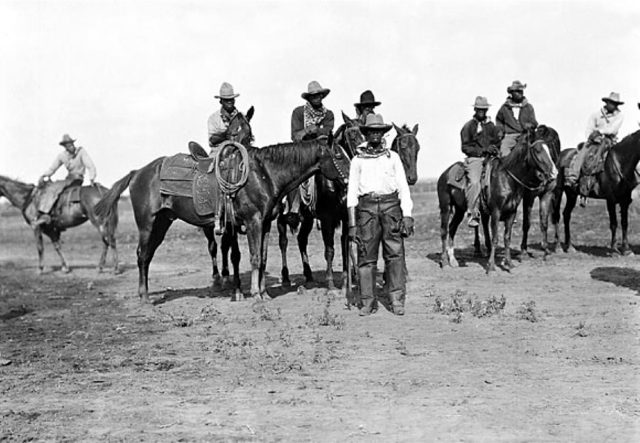

Bonham, Texas, 1913. By Texas State Historical Association, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

If your mental image of a cowboy is a sunburned white guy squinting into the distance while dramatic music swells, congratulations, you were successfully raised by Hollywood.

Because the real American West? It was far more diverse (and a whole lot more Black) than the movie version ever admitted.

Historians commonly estimate that roughly one in four cowboys were Black in the post–Civil War cattle-drive era. That’s not a fun little trivia fact. That’s a massive chunk of Western history that somehow got edited out of the mainstream canon.

In honor of Black History Month and in the spirit of Horse Nation’s favorite activity (learning something new while being mildly annoyed we weren’t taught it sooner), here’s what “The West” actually looked like, who built it, and how that legacy still shows up today in rodeo arenas, ranch work, and sports like cowboy mounted shooting.

Yes, “1 in 4” Is Real (and Here’s What That Means)

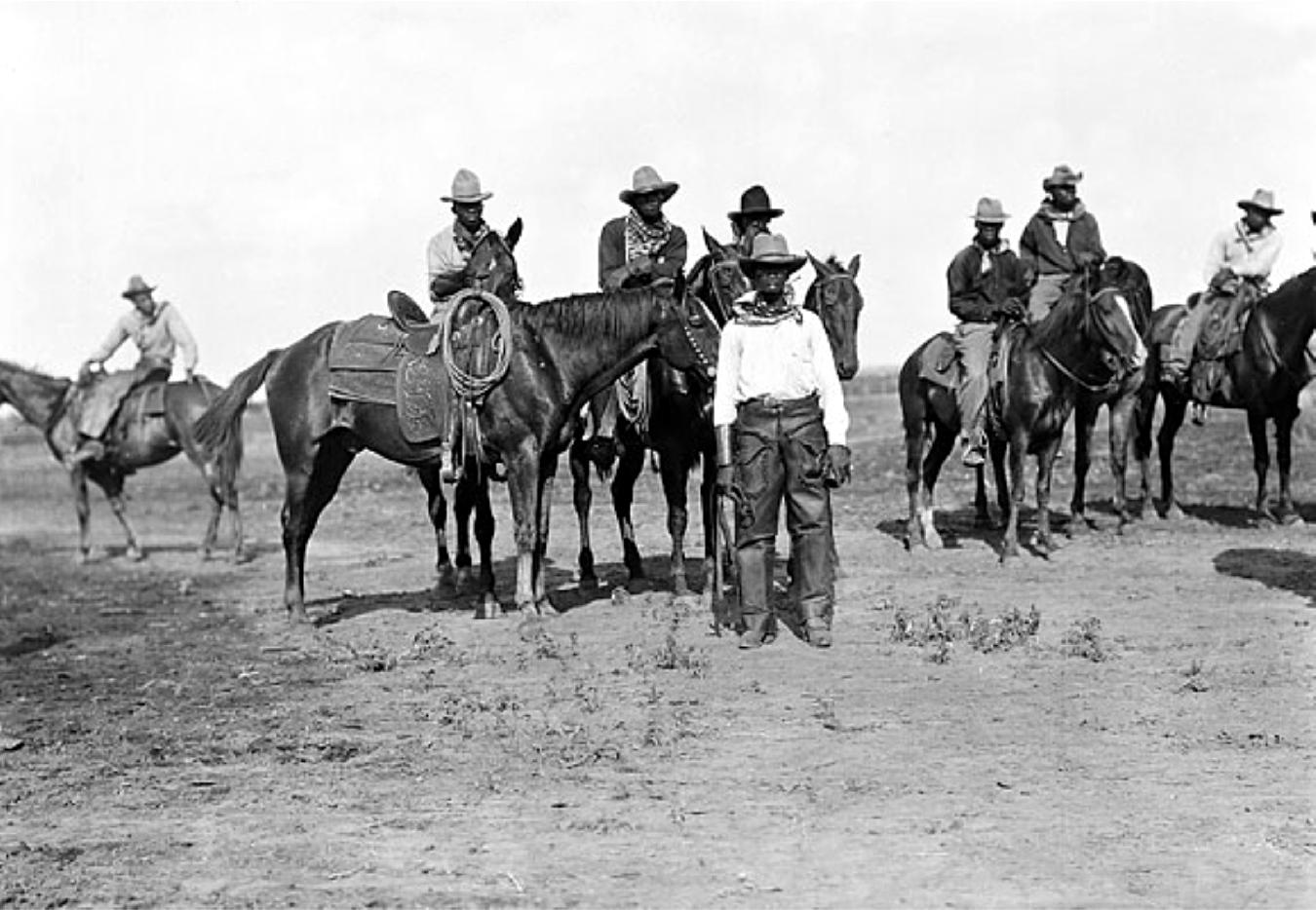

Solomon D. Butcher’s pioneer history of Custer County. 1901. Photo from Internet Archive Book Images, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

After the Civil War, the cattle industry exploded. Between roughly 1866 and 1895, cattle drives pushed millions of longhorns north from Texas to railheads in Kansas. And the labor force doing the riding, roping, and surviving on minimal sleep and questionable food?

A significant portion were Black cowboys, often estimated around 20–25% of cowhands.

Why?

Because many Black cowboys already had the skills. Enslaved people had long been forced into the work of livestock handling: breaking horses, tending cattle, building fences, and managing ranch labor.

African American rancher and two other men on a ranch near Goose Creek, Cherry County, Nebraska. Photo by Solomon D. Butcher, Public Domain, via Library of Congress.

After emancipation, that knowledge didn’t disappear — it became employable in a way that (sometimes) offered pay, mobility, and a life outside the rigid violence of the postwar South.

Was it equality? No. Was it freedom? Often (or at least more than what was available back East). And for some, it was a real path to independence.

Formerly Enslaved Men Didn’t Just “Join” Cattle Drives. They Made Them Work.

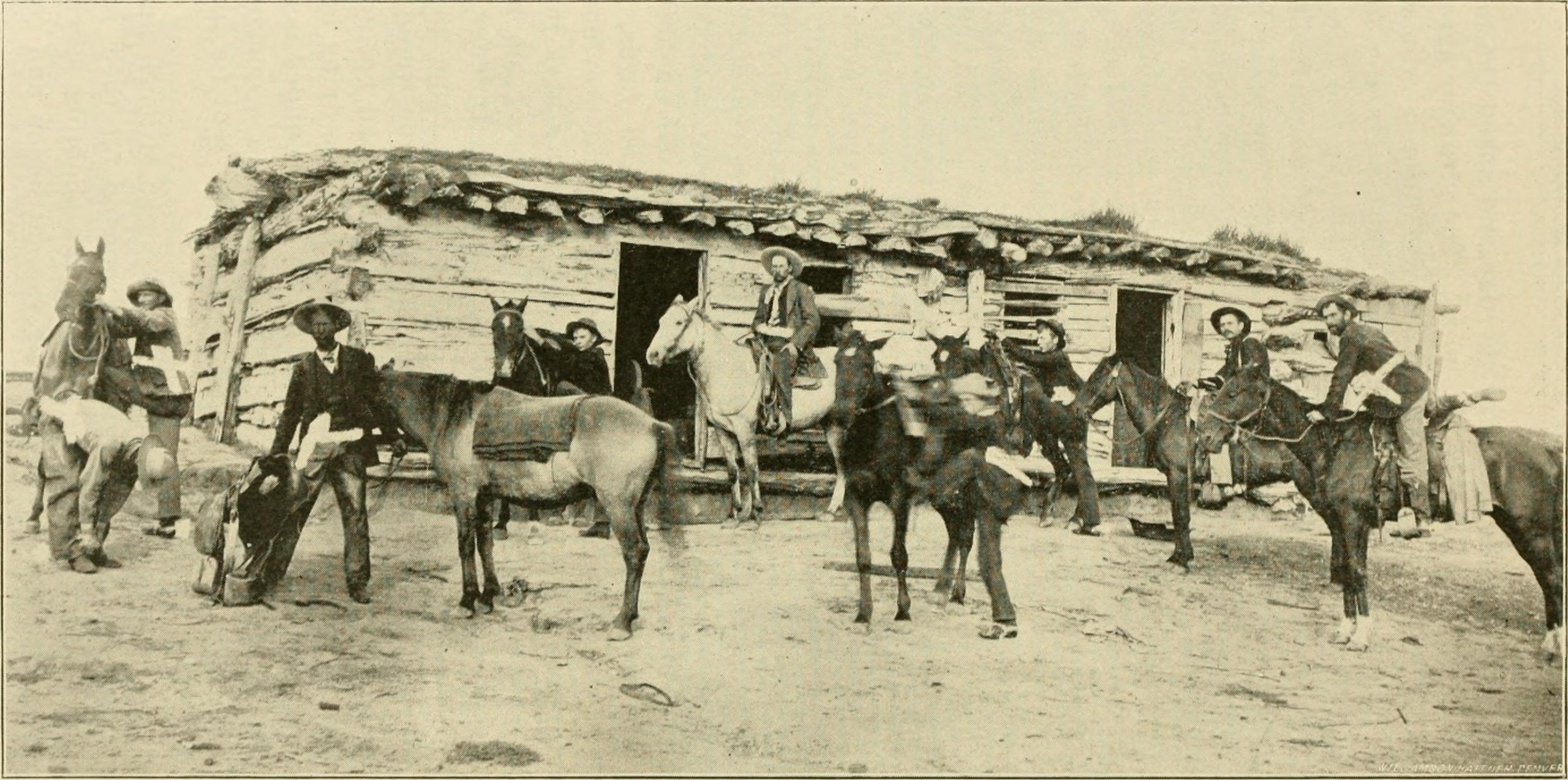

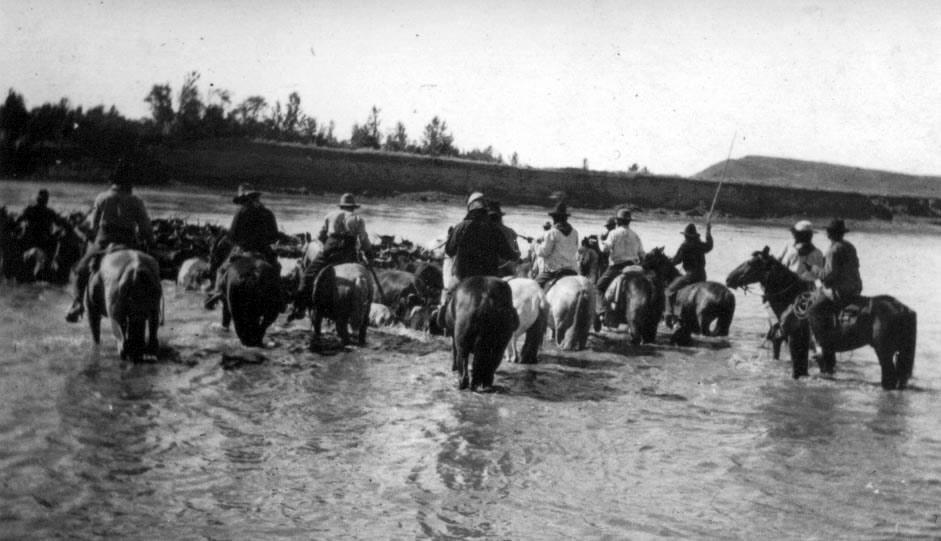

Cowboys crossing river at Grant-Kohrs Ranch, Montana, around 1910. Grant-Kohrs Ranch Historic Collection, bought by the National Park Service in 1972, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s easy to talk about Black cowboys like they were rare exceptions who showed up for a cameo and then vanished.

The truth is less romantic and more foundational: formerly enslaved men were part of the workforce that powered the cattle-drive economy, and many learned ranch skills while enslaved.

On a cattle drive, you needed riders who could:

- read livestock behavior fast

- handle a rope without getting anyone (human or bovine) killed

- ride long hours in terrible weather

- think clearly when things went sideways (which was constantly)

This wasn’t a place for the delicate. It was work that rewarded competence — and sometimes, that reality created slightly more room for Black cowboys to earn respect than in other industries of the time.

Although the romantic version of cowboy life gets all the screen time, the practical version matters: Black cowboys were doing the day-to-day riding, herding, and ranch labor that made “the West” function.

Bass Reeves: The Real-Life Legend Who Puts Most Fictional Lawmen to Shame

Bass Reeves. Photo is Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Now let’s talk about one of the most legendary horsemen/lawmen you should know: Bass Reeves.

Reeves was born into slavery in Arkansas in 1838, escaped during the Civil War, and later became one of the first Black deputy U.S. marshals west of the Mississippi, working primarily in what was then Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

He served for decades and became famous for his tracking skills, toughness, and sheer effectiveness. The Oklahoma Historical Society notes he worked 32 years as a deputy marshal in Indian Territory.

Depending on the source, you’ll see different numbers attached to him, but the consistent point is this: Reeves was an elite frontier lawman in a region known for violent outlaws, and he was doing it while being Black in post–Civil War America.

And yes, he rode. A lot. Over huge distances. In rough country. Often while facing down armed fugitives.

If that doesn’t count as “cowboy culture,” what does?

Want to learn about more famous Black cowboys? Amanda Ronan wrote a great piece, highlighting just a few.

So Why Don’t We See Black Cowboys in the Classic Story of the West?

Monogram Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Because Hollywood didn’t just miss them. Hollywood replaced them.

For much of the 20th century, mainstream Westerns centered white heroes and treated the West like an all-white stage where everyone else existed as background scenery (if they existed at all).

That erasure isn’t an accident. It’s a storytelling tradition that got repeated so often it became “truth” in the public imagination. The Smithsonian has covered how film history marginalized (or outright excluded) people of color from the classic Western myth, despite real history being far more diverse.

When pop culture did acknowledge Black cowboy history, it was often framed as a novelty rather than a correction — a “Wow, didn’t know that!” moment, instead of a “Why were we taught the wrong version?” moment.

The result: generations of people genuinely believing Black cowboys were rare, when in reality they were part of the backbone of the industry.

The Legacy Is Still Alive

Black Professional Cowboys & Cowgirls Association, Inc. presents Black Heritage Day in 2022. Photo by 2C2K Photography, CC, via Wikimedia Commons.

Here’s the part that matters for modern horse people: this isn’t just history-book content. Black Western culture isn’t extinct. It’s not a museum exhibit. It’s alive and still very much a thing.

Rodeo and ranch work are two areas in which Black Western culture is still readily apparent. Black cowboys have long competed in rodeo, and Black rodeo communities and events have helped preserve Western traditions even when mainstream spaces weren’t welcoming. (And if you’ve ever been to a rodeo, you know: skill doesn’t care what you look like. The clock and the livestock are equal-opportunity humblers.) And ranching still relies on the same core horsemanship values — feel, timing, grit, and the ability to get a job done when conditions are less than ideal. Those traditions didn’t magically begin with a movie montage. They were built by real working riders of many backgrounds, including Black cowboys.

And here’s the connection people miss: when we talk about “Western heritage,” we’re talking about a legacy that included Black cowboys from the beginning — even if modern media didn’t reflect that.

So if your local rodeo or ranch community is serious about honoring Western roots, the history has to be accurate, not just aesthetic.

The Real West Was Bigger Than the Myth

Black cowboys weren’t an exception. They were a presence.

They worked cattle drives. They trained horses. They rode hard country. They competed. They enforced the law. And they built pieces of the West that we still celebrate today — even when the popular story tries to pretend they weren’t there.

So maybe this Black History Month, we retire the single-story cowboy. Not because it’s trendy or woke, but because the truth is simply better.

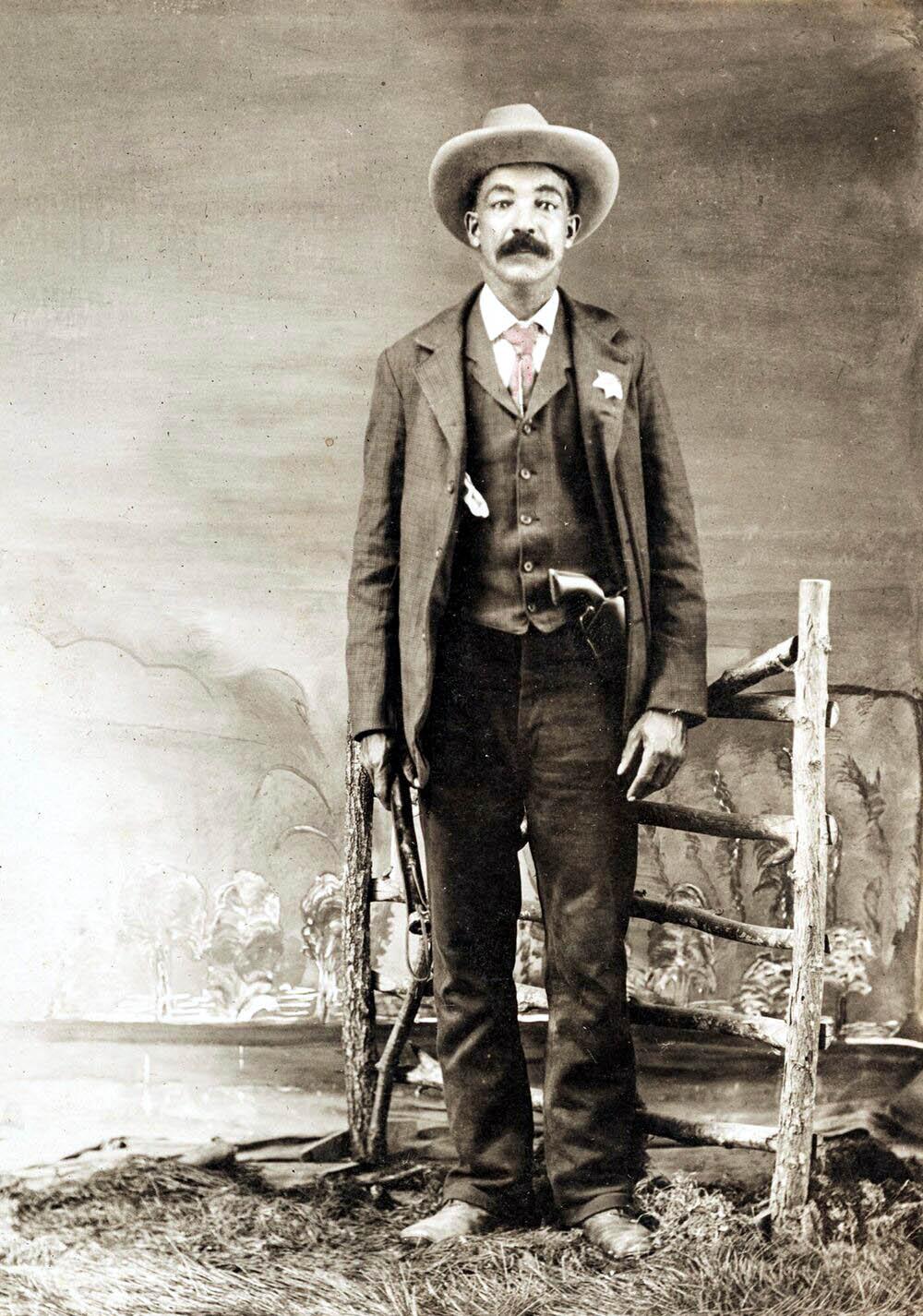

A Black sheriff in Idaho in 1903. Photo by Corbis, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sources:

- Nodjimbadem, Katie. “The Lesser-Known History of African-American Cowboys.” Smithsonian Magazine, Feb. 13, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lesser-known-history-african-american-cowboys-180962144/

- Library of Congress. “Black Cowboys at Home on the Range.” The Library of Congress Blog, March 11, 2022. https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2022/03/black-cowboys-at-home-on-the-range/.

- Sid Richardson Museum. “Free & Enslaved Black Cowboys.” Sid Richardson Museum Blog, April 10, 2023. https://sidrichardsonmuseum.org/free-enslaved-black-cowboys/